|

At Huj in the Sinai Desert at 1.30pm on November 8, 1917, 181 horses of the Worcester Yeomanry Cavalry - ridden by men armed with sabres - galloped into a force of 20,000 Turks, 21 German field guns and three Austrian 5.9 Howitzers. It was the final cavalry charge of the British Army. Darcy Harold Jones was the last survivor of that incredible charge, which scattered the Turkish army, helped to end 500 years of Ottoman occupation in Palestine and ultimately opened the way for the creation of Israel. He had never spoken about his experiences until he celebrated his 100th birthday. |

Corporal Darcy Jones, 21, and his friends Bill Wood and Reggie Smith from Malvern, had spent an enjoyable morning. The men of Major General Allenby's Egyptian Expeditionary Force usually stayed close to their depot because there was not enough water to go round, for them or their horses.

The men suffered from meagre rations, worse than the men in the European trenches. There was always malaria, white cholera, dysentry and heatstroke. In the searing heat and dust, even the healthy preferred to conserve their strength. But on November 8th, 1917, Darcy and his chums had been sent to scout further a field, crossing into the little valley below them.

On the side of the hill, they came upon a small hut. There seemed to be no one about; nothing stirred except for the buzzards and booted eagles always waiting above them. So, swords, drawn, they entered.

Inside they found Turkish women's underwear, all good quality and heavily embroidered and men's vests and pants, probably made in Berlin.

It was the boys' first reminder of anything female since they had left Blighty. Darcy began grabbing handfuls and stuffing it into his saddle bags, the others copied and, roaring with laughter, they turned back for the British camp. They galloped past the infantry, lying in long rows.

The men on the ground swore bitterly at the jokers on horseback as they whipped up sand into their faces. Amid the excitement, Darcy hardly heard Major General Allenby's order to prepare for a charge.

As the horseplay continued, he felt like a boy again, back in the safety of Britain. He'd been born in Worcester, November 26th, 1896. The British Empire ruled the world and his family was secure and happy. His father was a master potter and he had three elder brothers, Campbell, Harry and Frank, who had all enlisted, and a sister, Laurie.

Darcy had left school at 14 to become a laboratory technician. When he was 17 he'd also joined the Territorial Army, in the Worcester Yeomanry, and learned to ride with a sword.

His life had been one long game, but now he had the chance of real adventure of the type he'd read about in Boy's Own paper.

The animals were sent back to Ireland, but the men continued onwards aboard HMS Saturnia. They arrived in Egypt as infantry. In protest at being dismounted, they insisted on marching everywhere in their spurs.

In August 1915, they set off for the Dardanelles, the narrow channel between Asiatic and European Turkey, a vital passage between the Mediterranean and the Sea of Marmara, out to the Black Sea.

Australian and New Zealanders had originally been sent there to open up Winston Churchill's 'Eastern Front', protect Egypt and relieve pressure on the Russians.

A naval attack in February had been a disaster, but troops continued to pour in. When Darcy and his friends landed at Suvla bay on August 6th, the Turks were ready for them.

There, in the trenches, Darcy saw men die for the first time, but initially he was not dispirited. He got his first experience of 'Johnny Turk' and longed to be up and at him. But over the next four months, as his friends began to be shot down around him, his mood changed to frustration.

No one trusted the generals in charge - or Churchill's plan. The Dardanelles was Churchill's great disaster - a bloody episode in British military history comparable, in the ineptitude of its planning, to the Crimean War of 1853 - and it cost him his post as First Lord of the Admiralty.

But in the next theatre of war, Darcy came even closer to the Crimean campaign, taking part in an action that had echoes of the Charge of the Light Brigade at the Battle of Balaclava.

Between March and April 1917, the Turks tried to attack the Suez Canal by going through the desert, so the Yeomanry, along with the infantry and the Camel Corps, had to form a line, blocking the coast against them.

Over the next year Darcy led the life of a desert warrior. Days and nights were spent patrolling. And by November 1917, everyone sensed that there was something big in the air, but no one knew when or what it would be. They found out at noon on November 8th. Major General Allenby had decided that cavalry assistance was needed by the Londoners of the 60th Division, General O'Shea's 'Cockney infantry' and the Australian Mounted Infantry, who were being held up by two batteries of Austrian gunners occupying a fine position on the adjacent ridge. The Austrians and Turks were allies. From their position on the other side of the ridge, the Yeomanry could hear enemy shells, eight every 30 seconds, falling on the Londoners and Australians. Another battery of machine guns operating at right-angles was supplying raking fire across the British line.

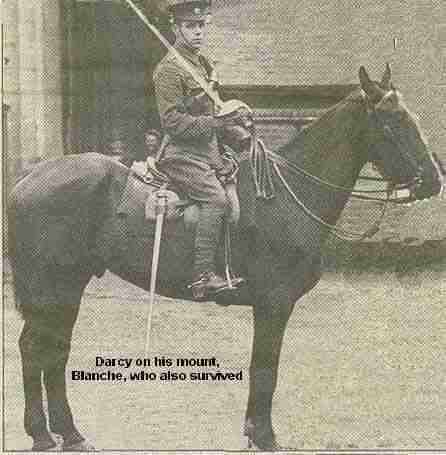

At 1.30pm Allenby ordered Lieutenant-Colonel Hugh Cheape, Captain Valentine, known as 'Val', and Major Bill Wiggin to assemble the men. Mounted on Blanche, armed with a sabre and a rifle, Darcy was more excited than he had ever been before. He moved forward to an indentation in the sand, and before them they could see the massed Austro-Turkish guns; they even saw the guns turn towards them. Valentine turned in his saddle, his face flushed. Darcy heard him shout: 'It's the guns we're after, lads.' And almost simultaneously he heard Lt-Col Cheape cry: 'Chaaarrrrge!'

Darcy cantered, then galloped at full pace, not thinking of anything, just feeling exhilarated. His horse and his drawn sword made him feel invincible. Like others, he had heard the rule a thousand times: Just point your weapon and the speed of your horse will do the rest.

A terrific fire was opening up on them by the enemy field guns, machine guns and rifles, at short range. The Midland horsemen dashed through the enemy left-flank guard, aiming for the field and heavy artillery pieces. Later it was reported that 'every artillery man was sabred by his piece'.

While Val lay dying on the battlefield, Colonel Cheape took some men and galloped round to the extreme right of the ridge and captured four camel guns three 5.9 guns and many prisoners.

Darcy and the Worcestershires attacked down the middle, between Val and Cheape's men. It was not the kind of charge the enemy were expecting. Unlike Balaclava , the British did not ride in formation, but in twos and threes, even wide apart. They looked more like Cossacks than regular cavalry, slashing the enemy and vanishing into their own dust.

Darcy heard a bang and realised that Wood's horse had been shot from under him. Nevertheless, Darcy rode on with the rest, on through a tornado of shot, shell and machine-gun fire. Austrian gunners fired so many shells that dud ones were going clean through the horses without exploding.

They reached the enemy guns with full-throated cheers, some using their swords like whips on the horses. The Turks seemed to freeze at the onslaught. As the British got among them and began to hack off heads and limbs, the guns roared and horses and men screamed.

Any Turk who stood still was cut down. Darcy felt he couldn't stop riding, he saw men fall down under his hooves, he rode them down. He saw them give up and run, abandoning their guns.

Around them the enemy scattered. The charge became a rout.

The whole action took 20 minutes: the most exhilarating few moments of Darcy's whole life.

After the charge there was silence. The Regiment bivouacked on the site of the captured positions for the night. Allenby sent his congratulations and men celebrated the capture of 12 guns. Others were delighted to find dumps of circular cakes of Turkish bread and sacks of compressed dates.

Thirty-six Yeomen were dead and four out of nine officers, including Val and Sergeant Allen, who had been with the Yeomanry since 1896. He was found dead, still holding his sword which was buried up to the hilt in an Austrian gunner. Fifty-seven men were wounded, and 110 horses lost.

The British took 100 prisoners, including a Syrian woman who was married to an Austrian officer.

Turkish corpses were piled into pyramids of 30 to 40. They quickly attracted flies and, to add to the discomfort, the terrible Khamsin wind, insufferably hot, started to blow like a blast-furnace, scorching dust-encrusted skins into sores and further drying already parched throats.

Some men dropped asleep, but Darcy and others set off into the desert to search for water of any kind, no matter how brackish. Five miles from Huj, at Nedjeli, some of them found foul water, full of black and yellow leeches. They gave it to the horses and drank it themselves with chlorine tablets. It tasted like something from Darcy's 'chem lab' back in Worcester.

At 7pm water carts arrived. For the men and horses that had remained at Huj it was their first drink for 50 hours. Early on November 9th, the British began to bury their dead. The bodies were put in a large pit, one mile from Huj, and marked with a cross.

Darcy still wasn't thinking, only feeling. Only later did he come to the conclusion: that he was glad to have been part of it, and satisfied that he and Blanche had come through unscathed.

Good humour and optimism remain with Darcy to this day, even though life has given him some hard knocks. Still extremely lively and cheerful, at the first mention of the cavalry charge he raises his arm as he would a sabre. At a special RAF Lyneham dinner given in his honour recently, a woman asked him how he likes spending his time and he immediately replied, 'making love'.

Back in Britain, he was fond of flying his small wooden biplane over his girlfriend Gertrud's garden so that he could wave to her. On one occasion his plane caught the tops of the trees, came down, and had to be rescued by some passing German prisoners of war.

After the Great War, he got a job in a pathology laboratory in Lewisham, south-east London. He and Gertrude married in 1920 and had a daughter, Dorothy, now 71. Their second child, a boy, died of pneumonia, aged eight. Not wanting Dorothy to be an only child, they had another daughter, but she was born mentally handicapped. Gertrude never recovered from these tragedies and suffered a nervous collapse, at one time refusing to go out of the house for 12 months.

Eventually Darcy, who was devoted to his younger daughter, retired early to look after his wife.

Darcy consoled himself by collecting stamps - he now has 40,000. He has always remained essentially 'a man's man', all his life playing all the sports he could, except tennis. He only gave up golf in his mid 90s. During World war II, he was commanding officer of 228 Air Training Squadron in Kent.

He has a painting of Gallipoli on one wall given to him by the Duke of Edinburgh, and another of the cavalry charge at Huj, but sometimes these days he forgets the details of his life as a desert warrior.

He becomes curious about why people are interested in him. If you tell him it's because he is famous, he immediately replies, with delight: 'You mean infamous, don't you?'

© Copyright 1996 Daily Mail

On April 10th, 1915, he had sailed from Bristol to Alexandria on the Wayfarer. It was torpedoed, but all the men were rescued. Before the boats sank some of the men returned to the stricken vessel and, despite great danger, rescued all 763 horses on board.

Sitting eating bully beef and getting his feet wet in the mud was not his idea of war. Darcy's idea of warfare was bound up with ideas of chivalry. It had to do with horses and sword play - it was the type of combat you could only find in the desert.

At Christmas, Darcy was glad to find himself back at Alexandria, and back in the saddle. He felt better, back in the desert, mounted on Blanche, his new steed. He would remember her with pride and affection all his life. He was happy again, despite the heat, the flies and disease. The camp was based over some ancient catacombs, right next to an outlet of the main drains of Alexandria. Many of the men went down with jaundice.

At Christmas, Darcy was glad to find himself back at Alexandria, and back in the saddle. He felt better, back in the desert, mounted on Blanche, his new steed. He would remember her with pride and affection all his life. He was happy again, despite the heat, the flies and disease. The camp was based over some ancient catacombs, right next to an outlet of the main drains of Alexandria. Many of the men went down with jaundice.

Val galloped about a length ahead of everyone else on a grey. Behind him men peeled off to charge 1,500 yards directly onto the guns, as if they were taking part in a game of toy soldiers. Darcy rode forward, next to his friend Bill Wood. As his sword arm came up and his spurs went in, the enemy adjusted their guns.

Val galloped about a length ahead of everyone else on a grey. Behind him men peeled off to charge 1,500 yards directly onto the guns, as if they were taking part in a game of toy soldiers. Darcy rode forward, next to his friend Bill Wood. As his sword arm came up and his spurs went in, the enemy adjusted their guns.

Captain Val, charged through an inferno of shells right onto the Turkish field battery, which was firing at point-blank range. His men took the guns and position and sabred all the gunners before they themselves were cut down.

After Huj, he gave up horses and went to Cairo to learn to fly. He got a commission to fly on April 1st, 1918.