|

|

Harry Thomas Munn1916 - 1997

|

|

|

Harry originally wrote the following piece for his Worcestershire Yeomanry Regimental archives. He had never spoken about the war to either his wife or daughter, and it was only after I had been his son-in-law for a number of years that he started to talk to me about them, mainly over a pint in the pub. I suppose it was a natural extension of our chats about life in the GPO (as it was then, BT now) where we both worked as telecom engineers.Harry is pictured here at La Panne, Belgium, in 1983. The Dunkirk Veterans Association organises a trip there every year where they are greeted as heroes, parade through the town wearing their medals and are guests of the Mayor at banquets and receptions held in their honour. NB: Sadly 2000 is to be the last year and the Dunkirk Veterans Association is to be wound up owing to falling numbers and increasing infirmity. Some more picture of Harry from early in the war, and at Dunkirk from one of the DVA visits.

|

What follows is Harry’s account in his own words. If anything I believe it to be an understatement of the facts, Harry was not given to exaggeration. Where Harry subsequently gave me additional information about an event I have included these as a to a separate window.

This is my remembrances of the above battery of the 53rd Anti-Tank Regt, and the officers and other ranks who served in it. The official history of the Regiment deals at length with the activities of the officers but says very little about the NCOs and ORs who made up the bulk of the regiment. I will try to correct this omission but it must be appreciated that when the Battery was in action in Belgium and Northern France my observations were confined to my own Troop, C Troop.

The Battery was mobilised on Friday 1st September 1939 and we all reported to the Drill Hall called "The Shrubbery" Kidderminster. In the evening of that day part 2 was issued and we were told we were now part of the Regular Army. It was a bit of an anti-climax when we were all sent home and told to report at 8am the next morning. At that time we were dressed in slacks, service Dress tunics, brown leather belts and also carried respirators, steel helmets and haversacks. Battledress had not yet been issued. There were no overcoats in the Regiment as those we had issued to us when joining the T.A. were withdrawn in July 39 for issue to the first batch of conscripted Militia. Our main armament, the 2pdr A/T Gun, was also in very short supply, only 3 guns per battery instead of 12. The rifles issued were 1917-18 vintage some with canker in the barrels. All-in-all we were very poorly dressed and equipped. Three weeks later after digging Air Raid Shelter trenches, cookhouse fatigues and some all night duties manning a Lewis gun on a tripod, our only defence against enemy aircraft, we moved to a Drill Hall in Wantage, Berkshire.

Here we settled down to the task of forming into what was to be our fighting units i.e. Battery Echelon A-B-C Troops. Then came a series of personnel changes. All ranks not 100% fit were taken out of the battery and transferred to other units. We lost amongst others the B.S.M. and Sgt. Quartermaster and all ranks under 18 were posted to other units. Baldwin Ltd steelworks asked for their personnel to be returned as essential workers, all were except George Bradley, Frank Barber, Bill Vaux and myself. Replacements in the form of regular army reservists were sent and the composition of the battery changed drastically. Many of the reservists were men who had served seven years in India and were on the whole pretty experienced soldiers. Their first action was to complain about the food which resulted in the posting of a regular cook to the battery named Bombardier Brough. After that there was a great improvement in the food and right through the fighting in France Bill Brough always produced a meal when we caught up with Battery H.Q. The reservists and the Territorials at first viewed each other with some suspicion but after getting to know one another better settled down together. Soon all the Territorials were using Hindu phrases learnt from the newcomers and turning upside down their ammo boots in the mornings, tapping them to get rid of scorpions!

During our stay at Wantage we went to three firing camps. One at Lark Hill then to Tilshead and finally to Lydd. At all these ranges we fired 2pdr guns that were already in position. At no time did we fire any of our guns. We also fired our rifles and Bren Gun which had been issued one per crew while we were at Tilshead. At Lydd in Kent it was a totally different type of range. As usual C Troop fired last and this enabled us to have a good look at the target run. The targets were tank silhouettes made of wood and canvas and were towed at speeds of about 25mph. This was far faster than anything we had fired at before. Frank Barber who was the layer on the C1 gun, and in my opinion one of the best in the battery, and myself who was a but that day was acting No 1 decided that when our turn came to fire we would catch the target at points on the run where it slowed down to turn. This we did scoring direct hits on two of the three targets. Unfortunately the Range Officer saw what we were doing and was far from pleased. Had we not both been greasy gunners at that time no doubt we would have lost our stripes. Next day the guns went into a nearby R.A.O.C. depot and as usual when anything of great interest was happening the gun crews were left outside. Frank and I wandered into the depot and looked at the soldiers working on the guns and were about to speak to them when we noticed that they were all WOIIs, and full sergeants were employed carrying the tools from gun to gun. We were about to get out fast when one of the WOs asked what the hell we wanted. When he learned they were our guns he allowed us to drain and refill the recuperating system under his supervision. This was useful instruction and came in handy when we refilled the systems in France.

Later in December 39 the battery went on embarkation leave and the advance party left Wantage early in January for Southampton. On the return of the battery from leave, C Troop commander was in charge of the advance party which consisted of most of the Limber Gunners and Drivers. The advance party sailed for France during the first week in January 40 and stayed in Vallicalville close to Le Havre. (On 12th January 1940 His Majesty King George VI inspected the Brigade in Wantage). The rest of the battery arrived some days later and in the coldest winter for many years. We moved north to Dourges where we stayed with a short break at Flines la Roche until May 1940 when the Germans invaded.

During this period known as the Phoney War many changes took place in the Battery. The original Battery Commander Major Gibbons was made 2i/c the Regiment and was replaced by The Battery Captain the Hon. John Lyttleton contracted pneumonia and was sent home. He was replaced by Captain Freeker. 2nd Lt D Woodward led A Troop, T.S.M Prosser led B Troop and Mr R.D.Hutton-Squire C Troop. B.S.M Danny Ireland changed places with B.S.M Whitehead from 210 Battery. All these changes did not alter the basic fact that we still had not got our full complement of A/T guns. It was only one month before we went into action that the Battery got its twelfth and final 2pdr.

Major R.Cartland was a man of very strong personality and of great ability. He did much to improve the welfare of the Battery introducing new procedures in food and a mess hall for all ranks below Sergeant. He worked out complicated movements for moving the Battery and training schemes were carried out to test these procedures. However all these movements depended on the despatch riders carrying orders from the Major to the various Troop commanders. This system broke down completely the first time it was used in action when the Germans invaded on 10th May 1940. The Battery moved to Antoing in Belgium where it carried out its secondary role protecting the 48th Division moving up, by Bren guns mounted on tripods being used against aircraft. We saw plenty of action during this period as enemy aircraft were over in large numbers every day. Whether the Bren gun was very effective as an A/A gun was very doubtful. and every gunner in the Battery was convinced his was the gun that scored the hit.

On the night of the 16th May the Battery moved up to Waterloo near the scene of the 1815 battle. We dug the 2pdrs into position and rode out the first raid by enemy aircraft. However in the afternoon of the 17th May C4 gun position was changed and Yorky Holmes the Bombardier was digging his new gun pit when a flight of Stuka bombers attacked our positions. Yorky’s gun crew C4 consisted of Phil Plevey, Bert Tanner, George Bradley who were all killed, Ron Bingham and Yorky Holmes had multiple shrapnel wounds. Also present when the attack came was Russ Heseford the Sergeant of C2 gun crew who had gone to assist in preparing the new position. Russ and Yorky were regular soldiers called up from the reserve and posted to the Regiment shortly after the outbreak of war. Both were strong personalities and well liked. Russ had a very interesting background having at one time served in the French Foreign Legion and in the Police Force. He was also killed outright. Yorky and Ron Bingham were eventually evacuated to England and later in the war Ron was killed while serving as an officer in the R.A.F. air crews. Major Cartland, Mr Hutton-Squire, Bdr. Charlie Rennie, Len Griffiths and Driver George helped to bury our dead. In the tradition of the Regiment they were wrapped in white sheets as apparently the first casualties of the Worcestershire Yeomanry in previous wars always were. Years later I visited a little churchyard at St Pieter Liews just off the Brussels motorway where these of our casualties are now buried. The three Yeomanry graves are in the front row centre of a much greater number of Belgian soldiers graves. One grave bears the name and number of Phil Plevey, the other two bear the inscription "Unknown Soldier of the Worcestershire Yeomanry". Note: Looking at the Commonwealth War Graves records it seems that only Phil Plevey is buried at St Pieter Liews. Bert Tanner, George Bradley and Ross Hesford (not 'Russ Heseford') are all buried at Ohain which is closer to the original action at Waterloo. Also while the three at Ohain are recorded as dying on 16th May 1940 (not 17th May) Phil Plevey died next day, so probably only injured in the attack and shipped back to a casualty station where he subsequently died. Phil and Bert were aged just 19.

That night disaster overtook the battery. What happened is still not clear. Mr Hutton-Squire withdrew C Troops remaining 3 guns from their positions in the middle of the night 17/18 May. As the troop moved off in the darkness C1 went into a ditch and extricated itself with great difficulty damaging the near side gun wheel in the process. Next morning we picked up four more guns of the Battery and 3 vehicles of Battery Echelon. George Prosser who was now Troop Sergeant C Troop arranged the vehicles in convoy order and Mr Hutton-Squire our only officer present was now Battery Commander. Mr Hutton-Squire brought the Battery back from Waterloo with great skill losing only the vehicle which had towed the ill-fated C4 gun which went off the road and had to be destroyed. Coming through the town of Tournai the damaged wheel of C1 gun came off. Now all the vehicles carried a spare gun wheel but none of them fitted the gun. This was a well known fact but no action was taken to put this right. George Prosser, Frank Barber and myself found some very large nails in a nearby deserted café and managed drive them through the broken rivets and this enabled us to get the gun back into France. Mr Hutton-Squire eventually found a workshop unit who turned the spare wheel on a lathe until it fitted in a fashion. After some days trying to establish contact with the Regiment we ended up at the Headquarters of what I believe was the 2nd Division. They made us very welcome, fed us and we had billets in the empty houses in the village. Our guns were placed in position guarding the roads into the village and apart from the inevitable air-raids it gave us the chance of a welcome rest. After three days Mr Hutton-Squire came to the gun site and instructed Harry "Smiler" Clark, the driver of the C1 gun crew, and myself to get some sleep as we would be moving later that evening. Smiler was a Canadian who had worked in Kidderminster before the war and joined the T.A in 1938. He was later to make a dramatic escape from a P.O.W. camp in Poland and was awarded the D.C.M. It was now the policy to move at night as the German Luftwaffe had complete command of the skies. When moving at night the driver and No 1 had to stay awake all night but the gun crew could snatch some fitful sleep in the back of the truck.

Just before dusk the convoy started to form up. C1 was to follow the Divisional Commander’s car and go into action on his instructions. However while waiting to move off Lt.Col. Medley, Regimental Commander, and Major Cartland came walking down the road. I called the detachment to attention and Major Cartland said "I reported you missing some days ago". I replied that we were all in the convoy and that Mr Hutton-Squire was further down. After speaking to Mr Hutton-Squire the Colonel had a word with the Divisional Commander and the 209 Battery was taken out of the convoy.

Once again Major Cartland had his battery all together for the first time since the night of 17/18 May and after one day holding a position on the Belgian border he led us on to Cassel. Cassel is a small town of Roman origin built on one of the very few areas of high ground in Northern France. Steep hills led in and out of the town and it was an ideal place to defend. Brigadier Somerset who commanded the Brigade put Major Cartland in charge of the anti-tank defences of the town and A.B.C Troops, 11 guns in all, were dug in around the town. The rest of the Regiment were formed into a flying column under the command of Col. Medley and sent to deal with "a few tanks" that had broken through our lines. One Troop of 211 Battery was left at Cassel to assist the 209 in the defence of the town. Several changes of position were made by C1 gun crew as the situation demanded until when Mr Hutton-Squire moved us up to a new position near the main Calais-Gravelines road. B Troop had been sent from Cassel under the command of Lieut. Freeker to escort a company of the Welsh Guards. We heard later that the Welsh Guards were the bodyguard of the GIC of the B.E.F. Major General Gort VC. C Troop took over the position vacated by B Troop and as we moved in we came under heavy mortar fire from the Germans down on the plain below. We quickly put our gun into the shallow gun pit used by the 2pdr which necessitated removing both wheels and took cover in two slit trenches. Our trench held the gun crew which consisted of Frank Barber, Bill Vaux and myself. The second trench contained the Bren gun manned by H.A. "Tiny" James and the Boyes rifle manned by W. Anthony a militia man who was recently posted to the gun crew. The driver Harry "Smiler" Clark had taken the vehicle some 100yds from the position where he could recover the gun and crew on my recall signal. Still under heavy mortar fire we stood looking out over the plain below and shortly afterwards we could see 24 tanks in line abreast coming towards our lines. They were too far away to be identified. Frank said "Do you think they are ours?" and I replied "I think it very bloody doubtful". As the tanks got nearer we could clearly see the Swastika flags on the front of each tank. Mr Hutton-Squire came to the position with Major Cartland saying to me "Tanks in your area Bombardier". I replied "I see them sir" and from then on they did not interfere with our handling of the situation.

Meanwhile the German tanks had reached a small wood at the base of the ridge and halted there out of sight of our position. Directly below us was a gap in the wood where we expected the attack to come from and sure enough three tanks came through the gap about 600 yds from the gun site. One was a fairly large tank armed with a gun and twin machine guns and two were smaller armed with machine guns and mortars. I gave the order "Take post" and we manned the 2pdr. As the No 1 I gave the orders using the open sights on the gun which enabled the No 3 layer Frank Barber to pick up and follow the tank with his telescopic sight. The loader No 2 Bill Vaux had loaded the gun and the next order was "Fire!". Now the 2pdr shell had a tracer base and this enabled you to see where it went. Our first shot went straight and true for its target but at almost the point of impact the tank dipped into a small trough in the ground and the shell passed in front of the turret. From our point of view this could not have been worse. The trace base enabled the German tank commander to know he was under attack and from what direction. His gun turret turned in our direction and he opened fire missing us by some fifty yards short of our position. Our next shot hit the tank just below the turret and failed to penetrate the armour but went up into the air like a rocket. We continued our duel with the tank. We fired, they moved, halted and fired back. After some 15 shells had been fired Bill Vaux the loader who could not see what was going on but knew from the lack of movement of the gun that we were still engaging the original target enquired "When are you going to hit the bloody thing?". By now the tank was less than 100 yds from our position and we still could not penetrate its armour. The only thing I could think of was that the wheels that propelled the tank tracks were unprotected and so I shouted to Frank "Hit the bastard in the tracks, Frank". The gun muzzle dipped slightly and just as the tank moved we fired hitting the track propulsion wheels and the tank halted abruptly swinging to one side. Still full of fight they turned their gun in our direction and fired again hitting the bank in front of the gun. Our next shell must have disabled the turret as they opened the escape hatch and ran for their lives back towards their lines. George Prosser our Troop Sergeant had left his Troop H.Q. when he saw we were about to engage the tanks and laid down by the gun taking pot shots with his rifle. He hit the last German to leave the tank who fell down by the side of his tank. The other two tanks that came through with the one we had just stopped were on the right and left of our position. I decided to engage the one on the left as it was close to the outskirts of the town and firing mortars at a target in our lines. It was a perfect target silhouetted against a small hillock. I gave the necessary commands - direction - range - and a zero lead fire. Frank pressed the firing pedal and this time the shell penetrated the exploded inside the tank and blew it into small pieces as its own ammunition went up. There were no survivors. The third tank had not moved from the point where we had first sighted it and its turret moved slowly round searching for our gun. I re-laid the gun on the new target, gave the order "Fire!". Bill Vaux had already loaded and Frank followed the tank traversing left and right as it searched for our position. Frank talked to himself as he followed the target, "Keep still you bastard" and as the tank paused for a second he fired, completely destroying this one as we had the previous one.

No more tanks were in our immediate vicinity and we waited to see if any more came through the gap in the woods we were defending. Heavy mortar fire was making our position very uncomfortable and we were about to return to our slit trenches when a Sergeant from the 2nd Gloucesters ran over to our gun pit. He was delighted we had stopped the tanks but pointing to a small cottage about 300yds to our left he told us another tank was holed up behind it having got this far without being seen. The Sergeant told me no one was in the cottage, the French family were long gone and his men who had been using the cottage had all gone into the trenches when the attack commenced. We opened fire on the cottage, one shell through each window and one through the thatched roof. The whole place went up in flames. We waited but no tank emerged. Later on our long march into captivity I met this Sergeant again and he told me that the tank was burnt out at the back of the cottage as a result of our attack.

Major Cartland who together with Mr Hutton-Squire and Mr D Woodward had observed this action from the very exposed position at the rear of the gun pit, came to me with new orders. He said we could leave the gun where it was and move to a temporary safer position or recall the towing vehicle and recover the gun in the usual way. No doubt he was aware of the difficulty we were having with the damaged wheel and did not wish to risk the gun crew out in the open for too long. We decided to recover the gun which we could do in normal circumstances in under a minute. However the damaged wheel proved difficult and it took both Frank and myself to get in on the axle leaving the whole crew and vehicle out in the open. We quickly hitched the gun to the towing hook and as we were on grass and facing up hill shouted to Smiler to drive on and ran pushing the truck through a gate in the wall to the comparative safety of the main road. Next day I returned to the gun pit. It contained many large fragments of mortar bombs and the top of a nearby tree had been blown off and was lying in the gun pit. Bill Vaux who was with me counted the empty shell cases, twenty-one in all. He considered it was too many for the net result of only, at that time, three confirmed tanks destroyed. He buried 17 empty shell cases in the slit trench. He then invited over the next few days all he could find to come and see our

When we got our gun and truck out on to the main road Major Cartland and Mr Hutton-Squire were discussing the resiting of the gun when a message came that tanks were attempting to break through a road block on the road we were now on. As an attack was imminent it was decided we would fire the gun on its wheels. This again was something we knew the drill for but had never done or seen done. It called for a fourth man in the crew whose job was to hold the gun spike used for lifting in the trail eye and stop the gun turning over on recoil. "Tiny" James the biggest man in our crew was detailed for the job and we went to action stations prepared to fire. We were more worried about what would happen after we fired than the threat of the approaching tank. Major Cartland moved a French 75 field gun alongside us manned by a crew of French officers. He then took over the Bren gun vacated by moving "Tiny" James and we all waited. Mr Hutton-Squire as always with complete disregard for his own safety had gone down towards the road block to see what was happening. Tension mounted and then an anti-climax as round the corner from the direction the tanks were expected came C Troop’s Dan R Len Griffiths on his motor bike. Now by this time Len was one of the few Dan R’s still riding his bike and as always he was full of the joys of spring. "Hello you shower of so and so’s" he greeted us and produced packets of cigarettes from his saddlebags for us all. About to throw a couple of packets to the Bren gunner he noticed for the first time that it was the Major. Throwing a very smart salute he apologised and saying that he knew the Major was a non-smoker like himself he gave him a large handful of 2oz bars of Cadbury’s chocolate. A runner came up from the road block with news that the tanks had withdrawn back to their own lines and the immediate crisis was over. Major Cartland called Len Griffiths over and instructed him to go to his H.Q. and take the B.S.M. and his staff to Regimental H.Q. This was the last we saw of him until after the war. He told me that after Dunkirk when the roll of the Regiment was called he was the only man to parade when C Troop was called. He was decorated with the M.M. for his exploits on the road back to Dunkirk. Later in the war after service in the Middle East he went to Burma. He was again decorated this time with the D.C.M. and although badly wounded survived the war. Len Griffiths was as far as I know the most decorated O.R. in the Worcestershire Yeomanry.

Apart from intermittent mortar bombing the attack on Cassel appeared to have petered out. Major Cartland gave us the up-to-date situation as he knew it and was far from optimistic about the situation as indeed none of us were. One of B Troop’s guns that had left the town that morning returned with the truck badly shot up and the gun disabled. Major Cartland sent Bombardier Matthews and the gun crew back to R.H.Q.

Shortly afterward Mr Hutton-Squire returned and after a conference between Major Cartland, Mr Woodward and Mr Hutton-Squire the guns in our sector were resited. C1 went back to a new position covering the same area where earlier it had seen action. The French 75 was nearby. C2 had been hit and was partially disabled. Bdr Jack Griffiths, Vic Sutton and Colin Lloyd were all OK. Sgt Bill Pugh and his crew were still in action positions lower down the Calais road.

Mr Woodward’s A Troop had done sterling work during the attack in positions adjoining the left flank of C Troop, Bdr "Cag" Davies stopping two tanks at point- blank range. Both tanks crews were killed outright. About this time the French 75 did a shoot against tanks down in the valley. Where the gunners were I do not know but both times the gun was manned it was by the French Colonel and his officers and W.O. This time they opened fire on a cross-roads down in the valley using armour piercing ammunition which was carried to the gun by two of our gunners, one of whom was "Smiler" Clark. The French Colonel observed the shoot through his binoculars and announced that they had hit and destroyed six tanks. Shortly afterwards he opened fire again at targets in the same area this time using shrapnel. One 2pdr gun operating in the area where C1 had been that morning and operated by its one remaining gunner knocked out five tanks. Apparently a sniper of the hiding in the town had picked off the gun crew one by one. The last survivor of the gun crew saw the tanks approaching along a sunken road. He bravely got into the layers seat, hit the first tank, turned his gun on the last tank in the line disabling it and blocked the other tanks in a position where they could not move. He then destroyed the three other tanks which were completely trapped. I regret I do not know his name but believe he was from the 13th A/T Regt. R.A. All in all some were destroyed on that afternoon.

Next morning the German infantry put in a rather half-hearted attack unsupported by artillery or tanks. This was easily repulsed by heavy machine-gun fire from the many Vickers machine guns located around the ridge. There had apparently been a store of Vickers guns at Cassel and the Glosters had brought them round the various units, set them up and given us a short instruction on how to fire them. So our remaining problem was the heavy mortar fire. Mr Hutton-Squire who on the previous day had left our lines to find out if the tanks were about to attack the road block we were defending told us he knew the position of the German mortar battery. Some two hours later they returned in very high spirits having destroyed the mortar battery without any casualties to themselves. They were full of praise for Mr Hutton-Squire who had led them to a perfect position for the attack and brought them back to our lines before the German infantry realised what had happened.

During the next few days we observed the activity down on the plain below us. The German troops were active but too far away for us to engage. At night we could see burning towns at our rear. They were Calais and Dunkirk. What we did not know was that we were nearly surrounded and cut off from the rest of the B.E.F. On the evening of the 29th May orders were given for the destruction of our guns and vehicles and with heavy hearts we went to Major Cartland’s H.Q. As we entered we were given cigarettes and a tin of corned beef by Mr Freeker. Major Cartland made a speech in which he explained our position and said the Brigade would leave Cassel on foot and attempt to reach our lines. No mention was made that the evacuation was already taking place at Dunkirk. He also said it was an "every man for himself" situation and any man who wished to make his own way was free to do so. All elected to follow the Major and armed with rifles, Brens and Mills bombs we set off through the burning town of Cassel. Leading the march and bringing up the rear were remnants of the Brigade’s two infantry regiments - The Glosters and The Ox and Bucks L.I., R.A. and R.E. personnel in the centre of the column. During the night we encountered enemy machine-gun fire and George Prosser and "Tiny" James were wounded but fortunately not seriously.

At dawn we found ourselves under heavy fire from infantry and tanks. Very heavy casualties were inflicted on our battery and to save further losses Major Cartland gave the order to surrender. At this point heavy firing was going on and Major Cartland was killed. Mr Hutton-Squire, Tommy Bunn who was the Major’s driver and myself were some distance from the rest of the battery. and shouting "Follow me Bombardier" stormed out of the ditch we were in and firing a Bren gun at a nearby tank was killed by the answering burst of fire from the tank. Tommy Bunn and myself reached a ditch on the far side of the field and came under heavy fire from the same tank. We knew we would not be taken prisoner by this tank crew and crawled along the ditch towards a gate into the next field. We jumped from the ditch and ran through the gateway right into the middle of a German patrol who already had several of our battery prisoner. "Halt!" shouted their N.C.O. and Tommy and I went into the bag.

Before leaving Maj.Gen Thorne visited the C-in-C who expressed his appreciation at the way the Division had carried out its role in defending the right flank. The gallant defence of Wormhoudt, Cassel, and Hazebrouck undoubtedly held up large enemy forces and contributed to the evacuation of the B.E.F.

There were units of the SS with the German regular army - Hitler's personal bodyguard in fact - and some of these were so enraged at being thwarted in their attempts to destroy the B.E.F. that they took to executing captured Allied soldiers. One of them put a pistol to Harry’s head, whereupon the N.C.O. Harry refers to above spoke sharply to him. What he said Harry never knew, but the SS officer thought better of it, and Harry credits him with having saved his life. Many others were not so fortunate. At Wormhout a massacre took place where the SS murdered over 60 Allied soldiers with stick-grenades, machine gun fire and finally setting fire to the barn where they were being held.

Harry spent the next five years in Prisoner-Of-War camp, first in Poland where he said conditions were harsh and the food was very poor, at one point . However security was relatively relaxed as they were so deep in enemy-held territory that escape was considered unlikely (although Harry "Smiler" Clark did, see above). They were even allowed out to work in the fields with the local population. For a long time it wasn't clear which Polish camp he was in - from first-hand accounts see here and here many Other Ranks captured at the same time as Harry were initially sent to Stalag VIB near the Dutch border in Germany, then in a series of forced marches and train journeys over several weeks to Stalag IIIB Lamsdorf (which is variously described as being in Germany or in Poland as it was just on the German side of the border at one time and did change hands from time to time), with some going to Stalag XXA Thorn, others were sent to Stalag IVB Muhlberg (Germany) and Stalag VIIIB Teschen (near Lamsdorf). Conditions at Lamsdorf are said to have been poor, better at Thorn. Working in the mines seems to have been a feature of Lamsdorf, which Harry never mentioned.

May 2024: I'm indebted to John West who has found Harry's questionaire completed by all POWs on their return which gives the details of the camps he was in:

At some time Harry was what he described as "a bit of a bad lad" (but never elaborated) and was transferred to Stalag 383 at Hochenfels near Regensburg, Bavaria - room 185 2 Company. Probably just as well - as the Russians approached from the East 80,000 (numbers vary between 30,000 and 300,000) Allied soldiers were forced to march westward across Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Germany in extreme winter conditions - The Long March, over about four months between January and April 1945, with an estimated 2,200 dying along the way. And whether being liberated by the Soviets in 1945 would have been a good thing or not as an alternative is debatable as some accounts say the Russians did not allow access to Allied prisoners for some time, using them as a 'bargaining chip' with America and the UK.

In Harry's papers is a photo of a family wedding in which he appears, and the back has a German Army stamp with a camp number and 'Gepruft' (checked, i.e. permission to keep the photo has been granted), so this must be pre-war and something he had throughout captivity. The camp number in the stamp looks like 'Oflag IIIC', which is curious. An Oflag would have been for officers, although some did change to Stalags with a different number. The Pegasus Archive has link from Oflag IIIC to a photo of Other Ranks with an almost identical stamp, saying the camp was at Lubben in Germany some 40km south of Berlin, and a similar distance from the Polish border. Wikipedia says Stalag 383 was previously named Oflag IIIC, but Forces War Records agrees with Pegasus that Oflag IIIC was at Lubben and states that Stalag 383 was previously Oflag IIID. However Pegasus does not have an entry for Oflag IIID, and neither does this Moosburg Online list of POW Camps.

I wrote to the Contact point of Moosburg Online and they have very kindly replied giving the following clarification of camp numbering:

"So it seems that Oflag III C was transferred from Lübben to Hohenfels in Sept/Oct 1942 where there had been an Oflag 78 before. This camp at Hohenfels seems to have been renamed Stalag 383 in 1943.

"I couldn't find any reference to an Oflag III D."

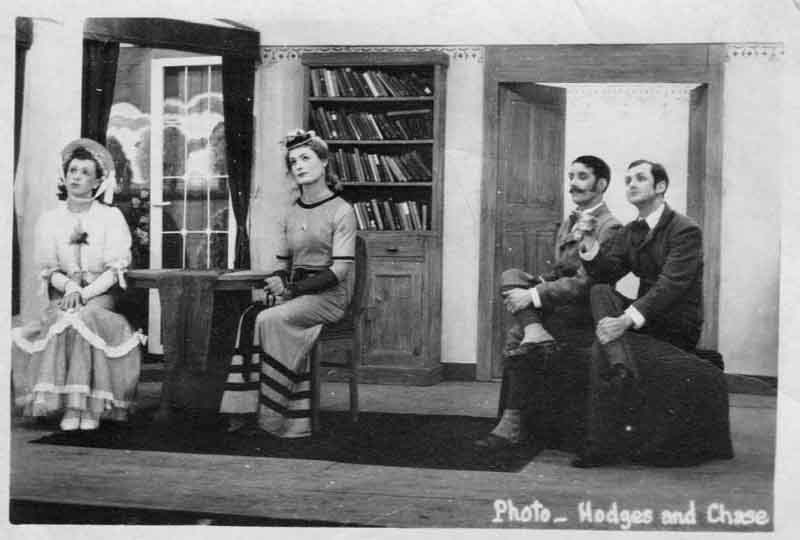

As depicted in "The Great Escape" life at Stalag 383 was highly organised by the prisoners, with theatres, dance halls, schools and even gambling dens and liquor stills (not to mention attempts). Believe it or not the two photographs below were taken during captivity and show the effort the POWs put into things like theatre scenery and costume:

Harry took part in productions of The Mikado and the Gondoliers at least being named in programmes produced at the time, and when I knew him still sang pieces from Gilbert and Sullivan comic-operas in private moments. For the story of how the camp theatre came into being click here.

For more pictures from Stalag 383 click here.

The site of Stalag 383 is now home to US Army Group Bavaria. Ironically, Google Maps shows rows of 'huts', not dissimilar to its earlier incarnation.

A Polish account of the 66th anniversary of the liberation of the POW camp Stalag III C ALT Drewitz, by James Piatkowski and Jozef Piatkowski.

One of the prisoners subsequently wrote a book (Barbed Wire - Memories of Stalag 383, M N M McKibbin and A Dallimore) of life in the camp, a copy of which Harry gave to me shortly before he died. I couldn't make out what the cover picture was - the central area was just blobs of colour. It was only when part way through the book and I discovered that the camp had 400 huts containing 6000 prisoners that I realised the cover picture represented a view of the camp from a watchtower, each 'blob' being a hut - a far cry from the few hundred prisoners depicted in "The Great Escape". The account is by turns horrifying and hilarious - horrifying for the cold and the starvation in the middle years before the Red Cross parcels started arriving, hilarious for the they scored over the guards. Once the parcels did start arriving they were better off in some respects than the guards, and were able to barter cigarettes for civilian clothing, cameras, radios, diamonds and even live ducks and sheep.

Like so many others Harry remained incarcerated for the remainder of the war in Europe. He was repatriated by Lancaster bomber in Operation Exodus, part of the Allied effort to bring home 354,000 ex-prisoners. Around 14,000 were flown home by Lancaster - although the majority of these were aircrew - most being brought back to RAF Cosford in the English Midlands (ironically where Harry's two grandchildren were born some 30 years later in the camp hospital). A great many were suffering from severe malnutrition and lice infestation.

More information on Operation Exodus here from:

At least by being transferred to a German camp Harry avoid The Long March that so many incarcerated in Poland had to endure, as the Nazis tried to escape westwards to avoid advancing Russian forces, taking as many prisoners with them as they could. Whether this was intended as a bargaining tool or they really thought they would be fighting on long enough for POWs left behind to be repatriated and returned to fighting strength isn't known, and even historians can't agree. Whatever the reasons, after suffering starvation and ill-treatment for four or five years in camps, being marched several hundred miles in freezing conditions with minimal food and shelter is, as Taking the Long Way Home says, a story of utter deprivation and unfathomable human resilience.

Even Stalag 383 inmates were subjected to a march in the closing days of the war, but of a completely different kind, paraphrased from 'Barbed Wire - memories of Stalag 383':

Those that were marched off on April 17th started with a picnic that lasted for several hours, and the Jerries were more concerned for their own safety than anything else so didn't worry much about hurrying things along, and by that evening they had only gone 2 miles. Then another troop of Germans approached from the rear and the first lot thought they had better get things moving and started shouting and firing over their heads, and they started marching for real. But next day the word went round and the prisoners all sat down and started having breakfast and the guards thought it was a real order and initially didn't do anything about it. Then more shouting and firing, until Nazi officers went round telling their men to cool it, and the march restarted in a more leisurely fashion. By this time the rumour was they were heading for Regensburg on the Danube, and the Nazi's last stand at Salzburg. After that night's camp the Nazi's started pleading with the men to get a move on as SS were in the area again. When they reached the Danube they were told the march was over and it was just a matter of waiting for the Americans, the Wehrmacht had had enough. 'White Angel' French nuns brought them parcels and food, and that was it. They had two weeks to put on weight, were flown by Dakota to Brussels, then by Lancaster to Surrey.

John West has created an excellent website telling the story of the 140 (5th London) Field Regiment, Royal Artillery including his father's exploits at Cassel, capture and incarceration in Poland. The Breakout describes the probable route from Cassel, ambush and capture near Watou of a large number of troops. The National Archives has several hundred German Capture cards available online for PoWs captured in the Cassel area, these for Cassel itself, for example. I have found over 800 so far but place names can have various spellings, e.g. three for Watou and four in the case of Cassel. The vast majority are in the first half of the alphabet by family name, which perhaps explains why I can't find Harry, they are still working through putting them online. I was hoping to find his record as amongst other things they give which camp each PoW was sent to.

John has written a book - 'The Psychiatrist: Conscript, Prisoner, Interpreter, Healer'. It is a novel but as factually correct as can be through much research inspired by a few family snippets of information about his father's wartime experiences at Cassel and his post-war life as a psychiatrist. I was privileged to receive a draft and gripped from the very beginning. The description of life for POWS in the mines of Silesia is harrowing, the retracing of their steps post-war emotional, the healing involved uplifting.

I have received an email from Valerie Jones of Retford, Notts. She has a copy of a St John Ambulance Certificate for Stalag 383 for Surgeon Instructor Major Brooke Moore dated 4 April 1944, found in the effects of Sergeant Thomas Canavan who was a POW for 6 years in that camp. If you know of Major Moore's family and they would like to have the certificate please contact Valerie direct.

February 2022: After coming across Harry's story Lisa Hughes has written to me about her father. Albert Tipping was also in 53 (Worcestershire Yeomanry) Anti-Tank Regt. serving under Major Cartland. After that his story is quite different to Harry's, but equally remarkable and well worth including here, with Lisa's kind permission.

Harry's probable position when he 'bagged' his four tanks

The 2 pdr gun of the type Harry used

Cassel, May 1940. Three pieces from: The Daily Telegraph of 1948; 'The Queen's Own Worcestershire Yeomanry 1922 - 1956'; and 'The Back Badge'.

The Glosters at Cassel

Two photos from Cassel after capture by the German army.

Cassel in November 2017

The Wormhout massacre

Bringing home World War Two’s ‘awkward lot’, also known as 'Prisoners of War'

The Worcestershire Regiment - Dunkirk 1940

Dark times for Worcestershire regiments in run-up to Dunkirk from the Worcester News

Worcestershire Yeomanry Cavalry (1794 - 1994) a history by Derek Woodward.

The final British Cavalry charge - Worcestershire Yeomanry November 8th 1917. The last survivor tells of the most exhilarating twenty minutes of his life.

Dunkirk 1940: Operation Dynamo, by Doug Dildy. Privileged to receive an inscribed copy from the author, part of Harry's action is quoted in the book, at

Qatia Day, Worcester, 2011. The author also donated to the Worcester Yeomanry the original artwork by Howard Gerrard depicting action at Cassel.

|

1940 Dunkirk Veterans' Association. From Vol. 42 No. 1 of the DVA Journal: "In 1867 the Ordnance Committee tried out a new portable cannon by strapping it broadside on the back of a horse tied to a post. The fuse was lit, the horse turned round to ascertain what the noise was about, and the shot went over Woolwich and fell in the dockyard. The poor horse was found dazed and lying flat on its stomach. The committee reported unanimously against any further trial." "When the first Mutiny Act was passed in 1689 a rider was added in that no Courts Martial should pass a sentence of death except between 0800 hrs and 1300 hrs. In those days of heavy drinking it was probably considered that the courts would not be in a fit state to decide on such a sentence after lunch." |

Other personal memories of WWII

Other personal memories of WWII

The book 'The Wormhoudt Massacre' is available from  The Military Collector and

The Military Collector and

Contemporary audio material

A video

Holt's Battlefield Tours

Imperial War Museum

World War II from BBC History 2000 Online

The History Channel

Subscribe to a Military magazine such as: